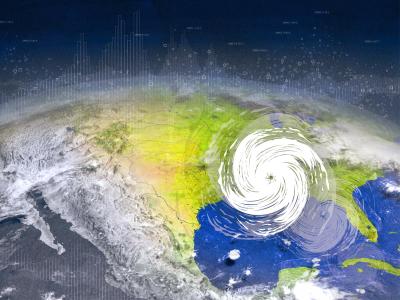

More Frequent Hurricanes Raise Risk to U.S. East and Gulf Coasts

Warming tropical waters can trigger changes in winds that both strengthen and push hurricanes to the U.S. East and Gulf coasts more often, boosting hurricane frequency by a third compared to current levels

Story by Brendan Bane; this story originally appeared on the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory website on April 7, 2023.

Hurricanes will become stronger and strike more often on the U.S. Gulf and lower East coasts, according to new research led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, who explored the influence of global warming on the damaging storms. Should current warming trends continue, they caution, landfalling hurricane frequency could rise by a third compared to current levels.

In a paper published in the journal Science Advances, researchers describe a previously unknown mechanism that fuels escalating risk to coastal residents.

Changes in the winds of Earth’s upper atmosphere—induced by a warming sea surface in the Eastern Pacific Ocean—are responsible for the projected boost in hurricane frequency in the coastal regions.

“What we found is that these wind changes have a double whammy effect,” said lead author and climate scientist Karthik Balaguru. “First, they steer storms closer to the U.S. East and Gulf coasts, which brings risk to the people who live there. But these same wind changes also reduce vertical wind shear near the coast, and that will ultimately strengthen coastal storms. When these two factors work together, it exacerbates the whole problem.”

Much work has been done to identify the changes that make storms more damaging in a warming world. For example, previous studies have projected that vertical wind shear—a force that typically dulls a hurricane by sapping its strength—will weaken under global warming. Weaken wind shear, said Balaguru, and you’ll strengthen storms.

Other research has projected that hurricanes may move more slowly, granting the storms more time to inflict harm. But, until now, such changes have largely been attributed to the general influence of global warming, with no mechanism identified.

“Global warming can mean a lot of different things,” said Balaguru. “We wanted to know exactly what, in a warmer world, is responsible for these changes. Uncovering the reason behind those changes, as we’ve done here, is both satisfying from a scientific standpoint, but also very important as we deepen our understanding of what influences extreme weather.”

More hurricanes, more risk

To understand how risk posed by hurricanes could look in the future, Balaguru needed one thing: more storms. Only a few hurricanes make landfall in the U.S. each year—far too few for robust analyses.

Researchers typically simulate hurricanes in models that represent Earth’s climate. But those simulations can quickly grow computationally expensive. The models must have sufficiently high resolution and, to generate the numbers needed to make trustworthy projections, researchers would have to perform many simulations of storms.

Balaguru and his coauthors instead developed a unique model known as RAFT. The advantage of RAFT lies in its ability to unravel the many factors that shape hurricanes, from the winds that steer storms to the warm waters from which they draw power. Meant to be combined with climate models, it can also generate many simulated storms, which makes robust statistical analyses possible.

This ability allowed Balaguru’s team to examine the relative significance of each contributing factor behind the changes. The resulting study, said Balaguru, marks the first time such an analysis has been carried out.

“We saw that storm frequency near the coast was changing,” said Balaguru. “But why? Is it because the storms are getting stronger? Is it because they’re heading more in that direction? Our approach helped us isolate the key variables at play and determine which was most important.”

RAFT generated hundreds of hurricane tracks: the paths that hurricanes take after they form over ocean waters. The results showed that, if current warming trends continue, storms would both strengthen and more frequently reach the East and Gulf coasts.

In ramping up the frequency of landfalling hurricanes, Balaguru’s team found that one factor stood more dominant than all others: wind.